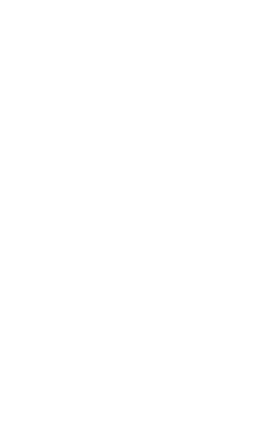

Firsthand accounts and archival images courtesy of Billy X Jennings and It's About Time: Panther Alumni Committee and Archive

A Brief History of the Black Panther Party in Berkeley

as told by Billy X Jennings, former Panther, founder of It's About Time: Panther Alumni Committee and Archive, and curator of "The Black Panther Party in Berkeley: An Archival Exhibit and 60th Anniversary Celebration" at the Central Library, Feb-May 2026

The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale.

Central Headquarters moved to 3106 Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley after the Oakland office was attacked by drunk police in 1968. It was located in Berkeley from 1968-1970. The main office was downstairs and the BPP newspaper was laid out upstairs. National Political Education classes were held there. Many members and staff were Berkeley High and UC Berkeley students and Black community members from Berkeley and North Oakland. The Black Panther Party opened a Free Medical Clinic in Berkeley, run by Dr. Tolbert Small and staffed by BPP members and volunteers (learn more about the clinic below). There was a West Berkeley BPP branch on 10th Street.

[Pictured: Black Panther Party National Headquarters, 3106 Shattuck Avenue, 1970]

In 1970, the National Headquarters moved to West Oakland. The Party kept the office on Shattuck, which housed the Panther School and the Berkeley NCCF (National Committee to Combat Fascism) led by Cec and Saul Levinson (learn more about the Levinsons below). Later, The NCCF moved to North Berkeley and the Merritt College Black Students Union moved in. They were fighting to stop Merritt College from moving up to the Oakland Hills.

While in Berkeley, the Black Panther Party helped establish the Basta Ya newspaper in support of Los Siete de a Raza. The NCCF, functioning as a BPP branch, opened a community center in North Berkeley, offering childcare, a first aid clinic, educational programs and films, a free plumbing service, and a skills exchange program among neighbors.

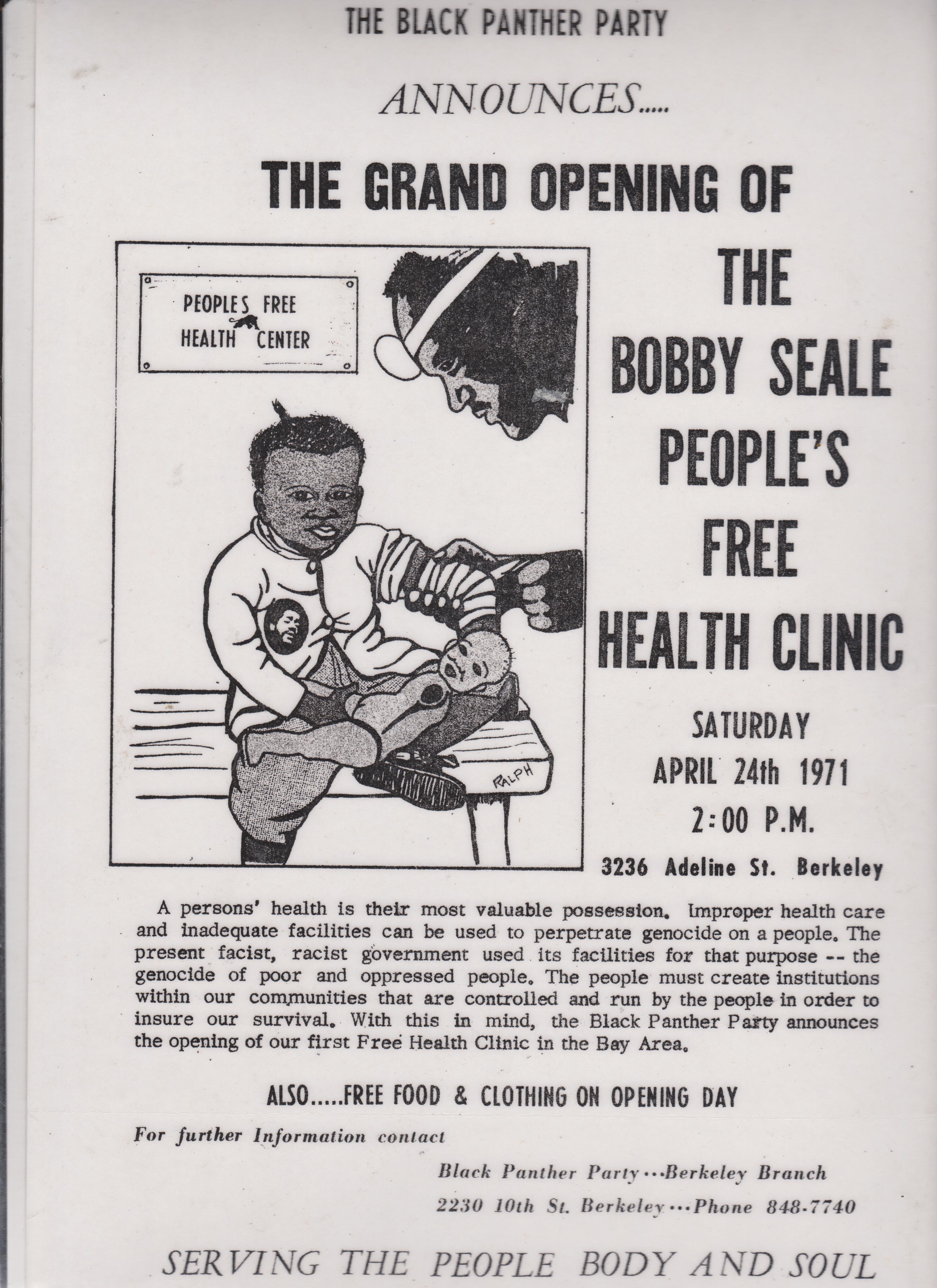

Cec and Saul Levinson, White Berkeley Residents and Panther Allies

Cec and Saul Levinson started working with the Black Panther Party in its early stages. They were a white couple with a history of civil rights and social justice activity who lived in Berkeley. Cec worked directly with Eldridge Cleaver to develop the Free Huey Committee. They travelled across the country building the Free Huey Movement.

[Pictured: Cec and Saul Levinson, Berkeley residents and Panther allies, founders of the National Committee to Combat Fascism, at the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1996]

After the Panther’s United Front Against Fascism Conference in 1969, the Levinson’s founded the Berkeley National Committee to Combat Fascism (NCCF). This was a group of white supporters who functioned as a BPP Branch under the direct leadership of the BPP. The Berkeley NCCF opened a community center in North Berkeley from which they ran a number of community programs including: a free plumbing service, childcare, a first aid station, educational films, and a skills exchange program among neighbors. They sold the Black Panther Newspaper and participated in Panther Party activities, such as political education classes, boycott lines, and helping get the paper out on Wednesday nights.

Their sons, David and Steven, were also involved in Panther activities. David was a part of the NCCF. He played saxophone in the Panther’s band, The Lumpen, and was a delegate when the Panthers sent a group to China, which influenced him to become a doctor. Steven was only eleven years old when he created the poster that was used in support of the Community Control of Police initiative in 1971.

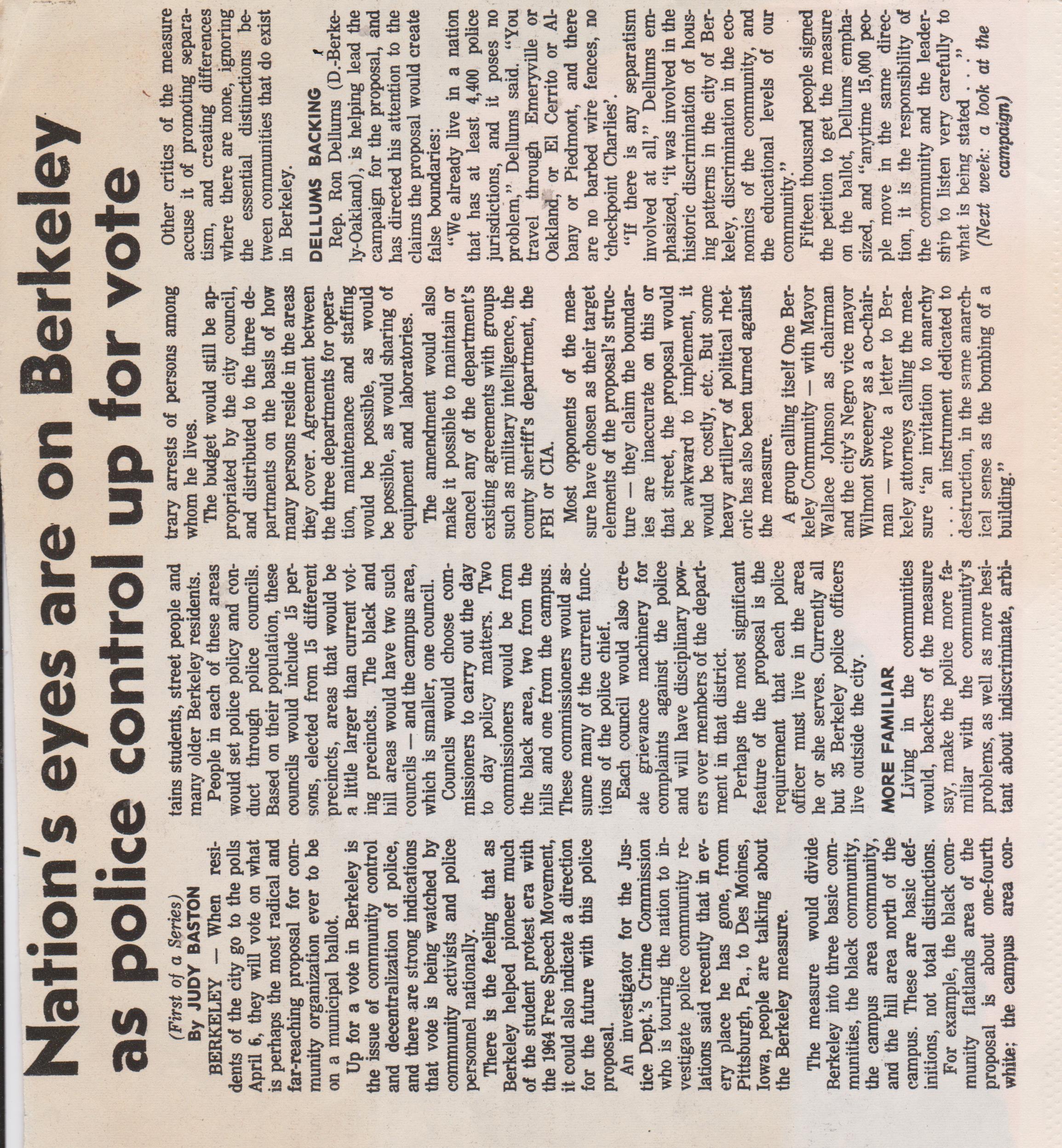

Community Control of Police Initiative

In the early 1970s, the Black Panther Party and the National Committee to Combat Fascism in Berkeley worked together to educate the public and get an initiative on the ballot to develop a community-based police department. This was the first such effort in the country, to put control of the police in the hands of the community. They collected over 15,000 signatures to get the initiative on the ballot in April, 1971. The initiative would have divided the department into three community-based subgroups: the flatlands, around the university, and the Berkeley hills. Police would be required to live in the community in which they worked. It would also establish a community review board with the ability to hire and fire police. This was a response to police brutality during antiwar demonstrations and the murder of James Rector during the struggle for People’s Park.

[Pictured: Berkeley Gazette news article about upcoming ballot initiative to make Berkeley the first municipality to have community control of police, 1972]

A group of Berkeley City Council candidates who supported the initiative formed a united front and ran as the April Coalition (as the election was in April). Although the initiative itself did not pass, all of the candidates who ran under the April Coalition banner were elected to office. There had been a well-funded campaign by police departments across the country to defeat this measure.

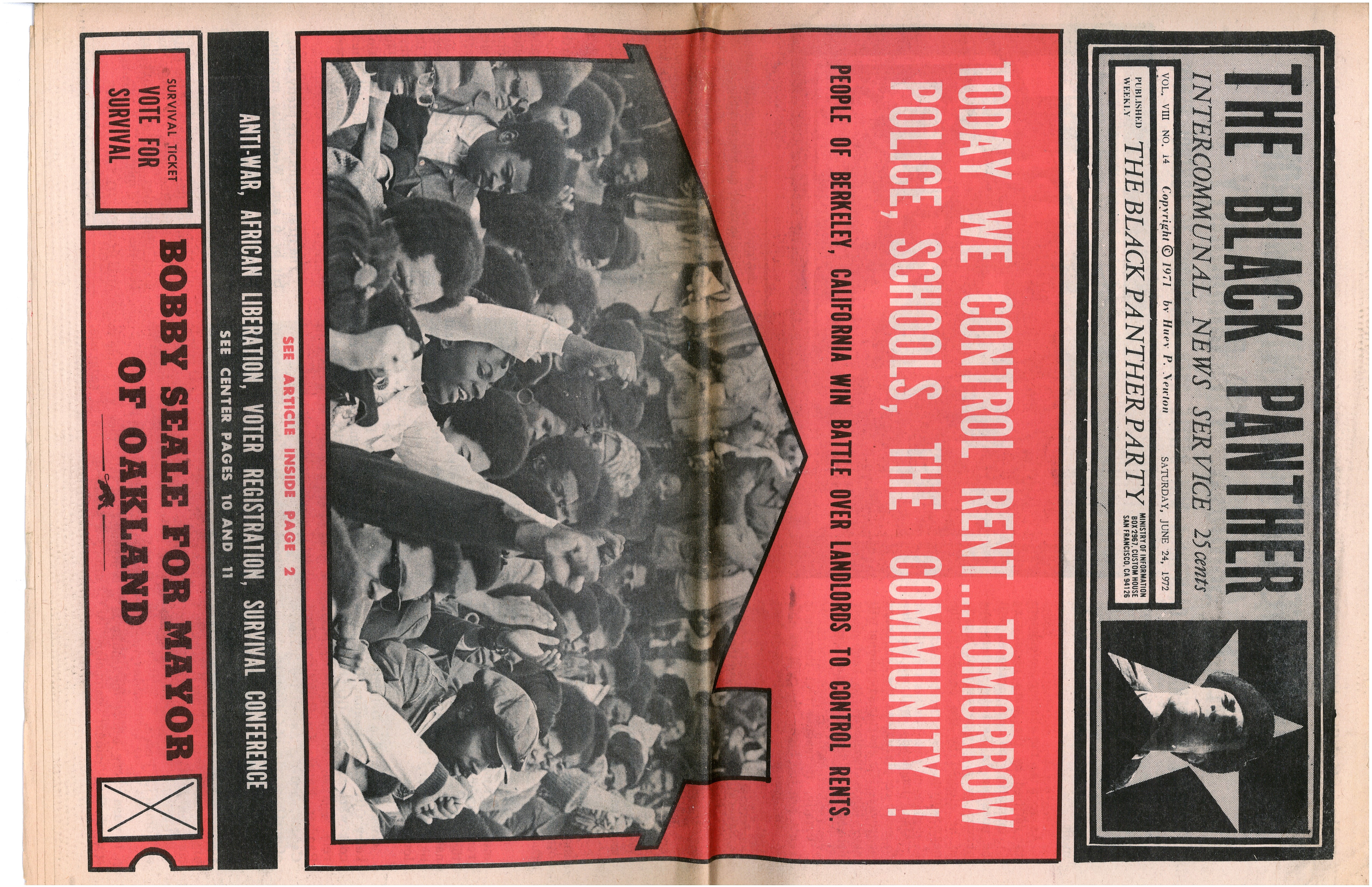

The People’s Free Health Clinic in Berkeley

as told by Sister Sheba, Panther Member & Clinic Worker

Before Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, running through North Oakland and South Berkeley was renamed, it was called Grove Street. That entire area was a vibrant part of the Black community, with a bank, small businesses, and storefronts. To the north was downtown Berkeley and to the south North and West Oakland. There were many working-class homes and a moderate number of apartments.

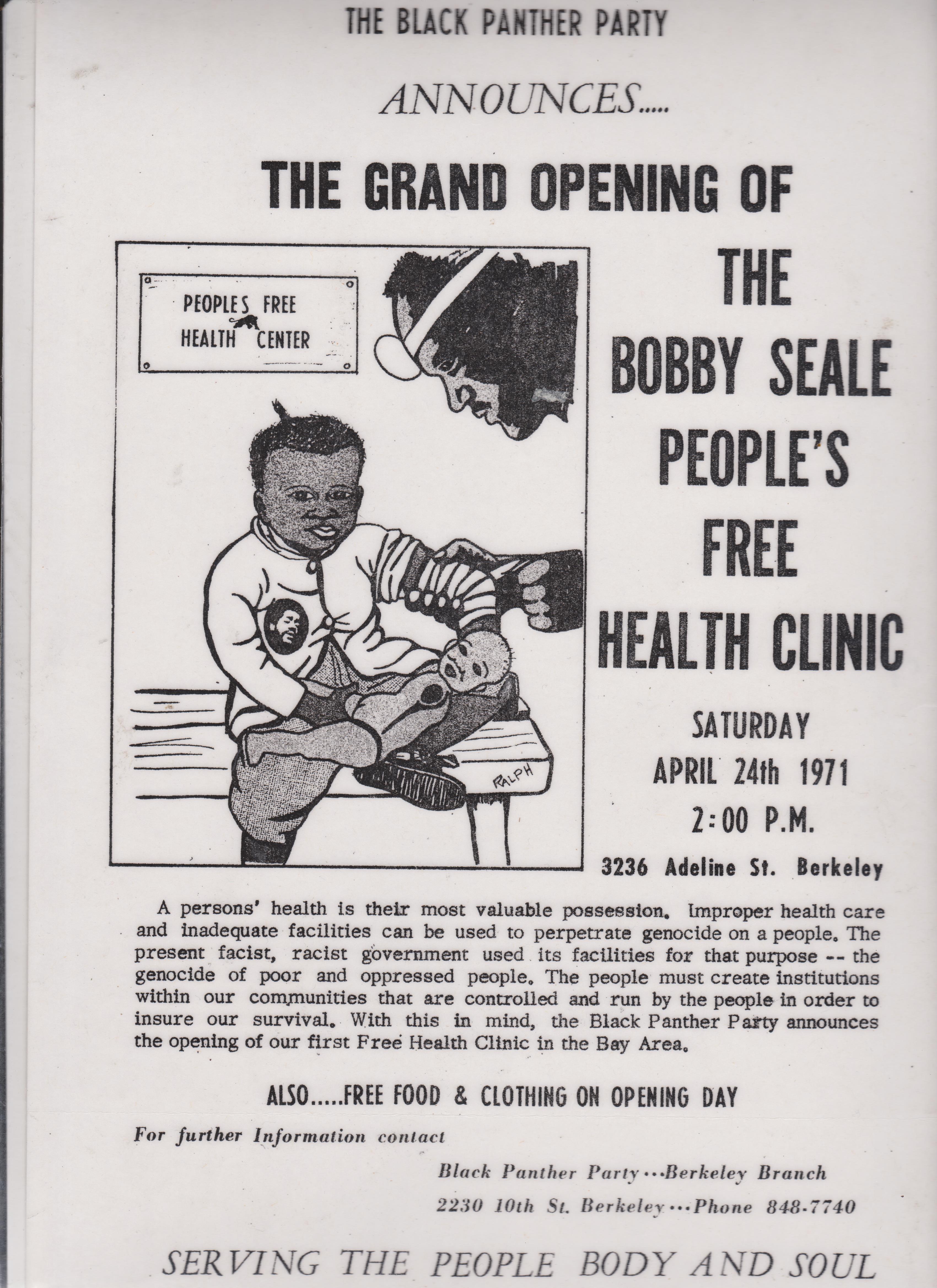

[Pictured: Announcement of the opening of the Bobby Seale Free Medical Clinic in Berkeley, 1971]

The storefront which became the People’s Free Health Clinic was in the center of this vibrant neighborhood. The first time I was sent to the clinic, it was a nearly empty store front. There were no exam rooms, but there were many cardboard boxes filled with pharmaceutical samples. Local physicians and “detailmen” (at that time, most pharmaceutical company representatives were men) donated samples to the clinic as the work of establishing the clinic progressed. My job that first day was to sort samples by class and aliment. Good thing I was a fan of chemistry!

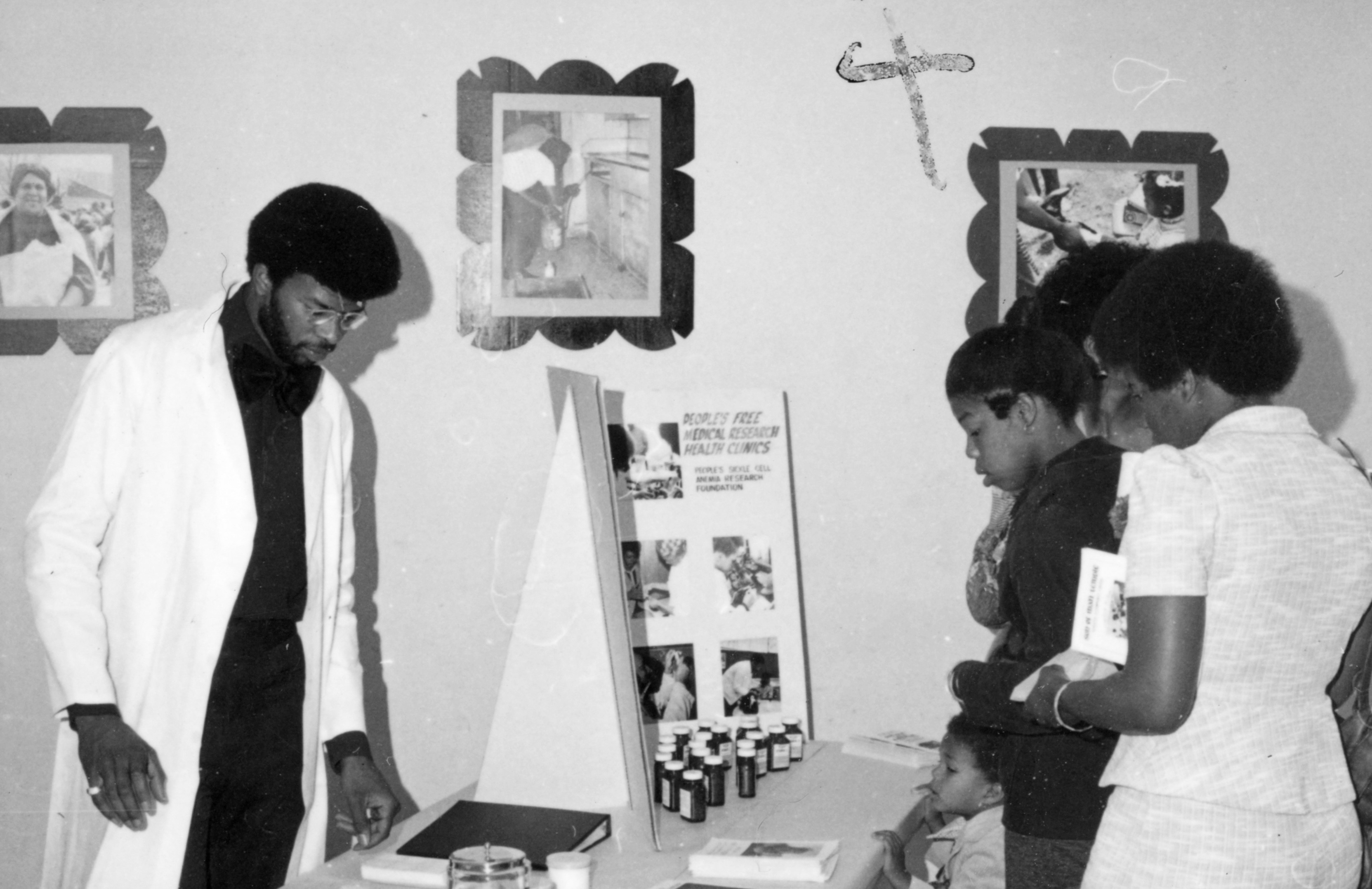

A few weeks later, I was pleased to meet Dr. Tolbert J. Small, MD. He was to be our head doctor. He got to work as soon as he got in the door, delineating spaces for exam rooms, check-in counter, pharmacy, and laboratory. As the weeks passed, carpentry work was done by Dr. Small, MD, Panthers, and community members. Curtains and signage went up. Dr. Small recruited other physicians and Interns from Alameda County’s Highland Hospital and scheduled days and hours of operation. The first name of the new clinic was the Bobby Seale People’s Free Health Clinic. Chairman Bobby Seale was still on trial in Connecticut. Once he was released from custody, the clinic was renamed the George Jackson People’s Free Health Clinic.

Like other BPP Survival Programs, the clinic was truly a community endeavor. My education was provided by nurses who lived in the neighborhood, Black doctors, interns and professionals in clinic administration, the Berkeley Free Clinic, and both Alameda County and City of Berkeley Health Departments. Both Public Health Departments provided vaccines, supplies, and information. The Berkeley Free Clinic helped me to acquire clinical laboratory skills.

[Pictured: Bill Elder, who worked at the medical clinic in Berkeley, seen here explaining sickle cell anemia, circa 1971]

Another thing that helped the clinic was the community work that was ongoing. Before I was sent to the storefront that was to become the People’s Free Health Clinic, I worked out of the West Berkeley Chapter of the BPP. I was a rank-and-file member after having been a dedicated community worker. Like everyone else, I sold newspapers, worked the Free Breakfast Program for School Children out of our office on 10th Street, and I also worked with the National Committee to Combat Fascism as monitors of the City Council. That chapter work was on-the-job training in community activism. Learning to read and understand the local legislative process, interacting and being part of the community to be legitimate representatives of community interests, and serving the community through the Breakfast Program was an irreplaceable educational experience.